It is impossible to pass by this object indifferently. For many people who are not familiar with the industrial traditions of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, the ruins visible from a distance at the crossroads bring to mind the ruins of an extraordinary palace.

This is proof of the craftsmanship, attachment to aesthetics and details that characterized the 19th-century creators of industrial plants.

Although the ruins that you can admire today come from the 19th century, the industrial traditions of Samsonów go back many centuries and are associated with the activities of the hosts of these lands - the bishops of Krakow.

We know that already at the end of the 16th century, a forge operated here, which belonged to Michał Niedźwiedz and Łukasz Samson (and as you can easily guess, the name of the whole village comes from the latter). A few years later, Bishop Piotr Tylicki brought here a family of Italian steelworkers, to whom he leased the local steelworks.

The next lessee, Jan Gibboni, completed the construction of the first blast furnace in 1644. Another furnace was commissioned by Bishop Kajetan Sołtyk in the 18th century.

The nationalization of the episcopal properties opened a new page in the history of Samsonów. In 1818, on the initiative of Stanisław Staszic, the construction of a new, much more modern plant began. Specialists from Poland and abroad were involved in the work. The name of the foundation - Józef - comes from the name of General Józef Zającek, i.e. the governor of the Kingdom of Poland.

The glassworks started operating in 1823. Its heart was a blast furnace. An iron foundry, warehouses for raw materials and manufactured products were also commissioned. Unfortunately, the plant was not spared by fires - the most dangerous of them significantly damaged the facility in 1866. The industrial plant itself changed owners. After World War II, it was declared a monument.

It is worth entering the area of the former steelworks and imagine what the plant looked like in its heyday. The most characteristic, round part of the building is the remnant of the blast furnace shaft casing. Above it, there is a gichtociągowa tower, from which the furnace was filled with charge.

Symmetrically around the ruins of the kiln, the remains of a pattern shop, a drying room and an enamel shop were spread out. History hunters will also find here former rooms for a steam engine, a coal mine or fragments of a section of the working canal.

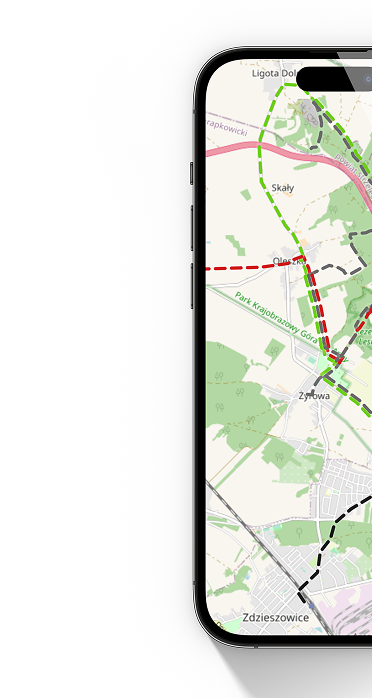

Polski

Polski